The right of eminent domain is enshrined in the Fifth Amendment, but the specific rights of property owners have required more elaboration over the years. To illustrate how things have come about and changed through the years, I’ve made a list of 7 milestone eminent domain cases in history – and what they mean for property owners like you right now.

#1: The first Supreme Court challenge to eminent domain

Kohl v. United States (1875)

The plaintiffs in the case had a leasehold in part of the property being taken. They contested the taking in court and demanded a separate trial for the value of their property. They lost and Cincinnati got its Post Office.

Takeaway

As the first eminent domain case to reach the U.S. Supreme Court, this case stands out. It was here that the long tradition of fighting back against government overreach and under-compensation began. This case was a loss for the plaintiff, which sets the tone for how difficult these cases can be.

#2: Due process and just compensation for your property

Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad Company v. Chicago (1897)

The Illinois Supreme Court connected the eminent domain authority of the Fifth Amendment with the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Essentially, this is the case that determined that due process is owed to property owners in eminent domain cases, and the state has to provide just compensation for seized property.

Ironically, the court found that the $1 award was, in fact, just compensation in this case.

Takeaway

As a private property owner, you cannot simply refuse eminent domain. Just compensation is generally your only recourse. This decision had a ripple effect through the court system, and helped ensure that the government cannot simply seize property without paying you fair compensation.

#3: Clarifying what a “taking” really means

United States v. Lynah (1903)

If nearby construction of government facilities inadvertently destroyed your property, did it technically take your property under eminent domain law? That was the question raised by Lynah. The government facilities in question here were dams and other controls along the Savannah River, designed to make the river more navigable and productive. The changes ended up flooding a 420-acre portion of a plantation used for growing rice. As the water level rose, the land became unusable.

The owner sued, and the case reached the Supreme Court. The court sided with the owner, ruling that it was an “inverse” eminent domain taking and awarding a fair market value of $10,000 as just compensation.

Takeaway

This case set an important standard – the government can’t simply destroy neighboring properties as a result of its activities even if it does not directly damage, build on, or modify those properties. Damage to private property can be an eminent domain taking, even if the government never directly touches it.

Learn More: Inverse Condemnation

#4: Limiting use is not necessarily the same as a taking

Penn Central Transportation Company v. New York City (1978)

The Supreme Court ruled that the city had not taken the land or the property rights. The effect was akin to zoning law – it simply limited certain types of construction while allowing the owner to gainfully use the space in other ways.

Takeaway

This case underlines that, while the government cannot take your property without compensation, your property rights can be regulated. The city wanted to reasonably regulate the land above Grand Central Terminal to preserve the terminal as a landmark, not take the property (or part of it) for public use – a necessary condition of eminent domain law.

Note: Every case is unique. What’s a simple zoning regulation in one case can be a compensable taking in another case. Don’t miss out on possible compensation. Get a no-obligation, no-cost case evaluation.

#5: Economic development vs. public purpose

Kelo v. City of New London (2005)

One of the most controversial examples of eminent domain, Kelo and its consequences still ripple through eminent domain today. The City of New London, CT, having just tempted pharma giant Pfizer to build a facility in the area with tax breaks, decided that the neighborhood of Fort Trumbull could produce greater economic benefits if it were redeveloped.

The local government gave its eminent domain powers to a private developer, the New London Development Corporation, which proceeded to take private properties in order to redevelop them.

NOTE: The right to exercise eminent domain can be given to private entities – it happens all the time. Utilities are the most obvious example. But this case raised a unique issue.

The question that arose was this: Could the government call it “public use” if it gives its power to acquire land to a private entity for economic redevelopment? The Supreme Court, in a split 5-4 decision, confirmed that the government could do so, ruling against the homeowners in the case.

Takeaway

The power to seize private land is one of the most frightening ones the government has. The Kelo ruling triggered a wave of questions about the influence of private interests in eminent domain and raised concerns about landowner rights nationwide. In the end, the Fort Trumbull neighborhood was bulldozed, but the development stalled and the land sat vacant for years, and Pfizer closed its facility just before the tax breaks ended.

Forty-seven states reacted to the ruling by strengthening their eminent domain laws to protect private property owners from abuse. A dozen states amended their constitutions to prevent the use of eminent domain for private gain.

NOTE: For a unique example of eminent domain being used to take private property and give it to other private citizens, check out Hawaii Housing Authority v. Midkiff.

Examples of Eminent Domain in Georgia

The Supreme Court ruling in Kelo almost went out of its way to indicate that states could pass laws restricting eminent domain. Georgia lawmakers reacted quickly, and the Landowner’s Bill of Rights was signed into law in 2006. The goal was to clearly define, and prevent the abuse of, the power of eminent domain.

Two cases have arisen since the passing of the law that demonstrate how the courts’ interpretations can impact and effectively control eminent domain power in Georgia. One case was about whether “public use” had to be proved or disproved. The other was about property appraisals and the intent of the law. They’re the 6th and 7th cases on my list.

#6: Condemning authorities must prove the taking is for public use

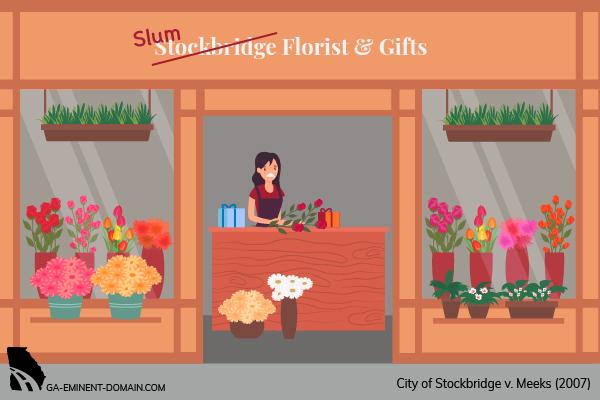

City of Stockbridge v. Meeks (2007)

Stockbridge Florist and Gifts, Inc. was the Meeks’ family business. Originally, the City of Stockbridge and the Meeks agreed that the city would get the property in exchange for space in a new development close by. But when the city scrapped the new project idea and instead moved to take the property through eminent domain, a bitter struggle began.

The city ultimately designated the area as a slum under Georgia’s Urban Redevelopment Law and took the land the florist shop was on without explaining the “public purpose” behind it.

The case made it to the Georgia Court of Appeals, where Stockbridge tried to argue that it didn’t need to explain the public purpose of its taking – that the Meeks had to prove the taking wasn’t for public use. The court wasn’t having it, and the Meeks won.

Takeaway

This is a complex case, but the effect is fairly straightforward. The city tried to place the burden of disproving public use on the private owner – which the court found absurd. The burden of proof for “public use” in Georgia is on the government entity or utility that is taking the privately owned land.

#7: Fair market value and mandatory appraisals

Summerour v. City of Marietta (2017)

The passage of the Landowner’s Bill of Rights was a clear response to Kelo, and the courts were paying attention. In this case, the city of Marietta wanted to buy a property to build a public park, but the property was occupied by its owner and his grocery store.

Before invoking its eminent domain powers, the city tried to acquire the property by simply buying it. It had the property appraised and used the appraisal to send an offer to the owner. It did this multiple times until, in 2013, the owner responded that the offer was low. This led to the owner hiring an attorney, more failed negotiations, and eventually a condemnation and a special hearing, which ruled for the city. The owner appealed.

The Georgia Supreme Court heard the case. As part of its argument, the city argued that the law did not require it to provide an appraisal, but merely suggested it. The court disagreed and added:

“The text, structure, and history of the statute as a whole indicate that this statutory scheme is to protect property owners from abuse of the power of eminent domain at all stages of the condemnation process.”

The court ruled for the owner, Summerour.

Takeaway

Private property is, for most people, their largest and most important investment. It’s their home, their business, or both. The Georgia Supreme Court, in this case, directed the law to be interpreted very broadly. The ruling places a greater burden on condemning authorities not only in providing appraisals but at every stage of the eminent domain process.

Major Takeaway: Eminent domain cases are complex, but an attorney can help you navigate yours

The cases above all reflect major changes and developments in eminent domain law. While most cases won’t make it to any court, much less the Supreme Court, it’s vital to understand that the law is alive, and always changing. That’s one of the reasons having an attorney to represent you is so important.

If your private property is being taken to build a road, utility, school, or any other government facilities, don’t just assume that the offer you receive represents just compensation. Local governments and utilities are like any other buyer – they want to buy your property for as little as possible. In my experience, the first offer is almost always too low.

And though you may be compelled to sell your property, you aren’t required to accept an unfair offer.

Call an Experienced Eminent Domain Attorney

Protect your eminent domain rights with an experienced attorney. Four of our attorneys formerly worked for a state Department of Transportation, handling some of their most important cases. We’ve handled hundreds – likely thousands – of eminent domain cases in our careers combined and we try to ensure property owners like you aren’t leaving money on the table.

Since our firm began, we’ve helped our clients get an average of 3x more than the initial offer for their property – sometimes much more.1

We have the resources and relationships to move your case forward and fight for maximum compensation. Call us at 1-888-391-1339 or contact us online right now for a free case evaluation.